The first thing we do when we start a project is to establish a baseline. It means that before we do anything else, we take measurements to determine how much carbon is being captured and sequestered in the project’s soil.

Next, we measure for additionality (the added carbon capture and sequestration) our plants and processes have on the project land, and we take four measurements over the life of the project. Then we share our before and after measurements with one of the oldest offset registries for carbon markets.

This process of measuring from baseline to additionality and reporting it is what establishes quality carbon credits. We always thought that this process was the right way to run our nature-based projects and we’ve done it like that since 2019.

Beyond the additionality of carbon we capture and sequester, our process restores and enriches the soil, improves the water cycle and increases biodiversity. These benefits are referred to as regenerative agriculture.

The baseline of the climate crisis

In the spirit of baselines, I wanted to offer my baseline (my quick history and current state) of the climate crisis, nature-based solutions and the carbon credits market, along with what has and hasn’t happened since we first identified the pattern of climate change.

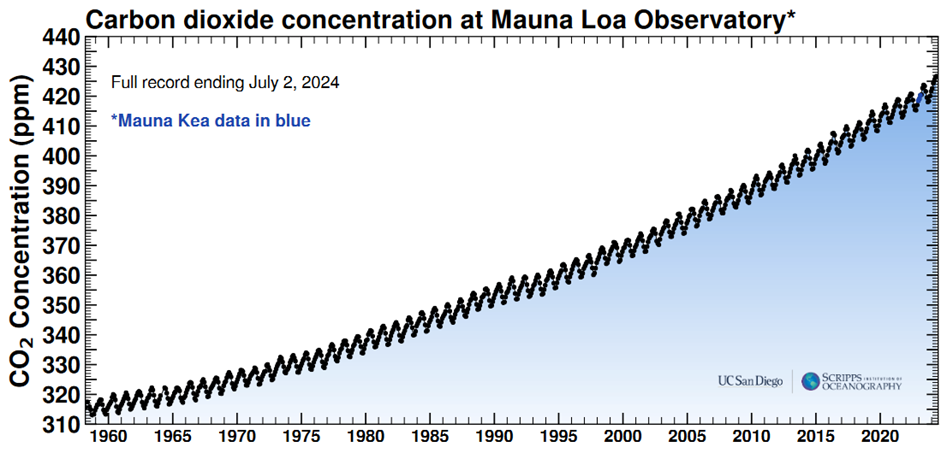

In 1958, Charles David Keeling started collecting carbon dioxide samples and plotting levels at a base two miles above sea level in Mauan Loa, Hawaii. Based on his samples, Keeling realized that the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was growing. When he started his project, CO2 levels in the atmosphere were 313 parts per million. Now, they’re more than 420 ppm.

Keeling’s measurements were the first proof that CO2 levels in the atmosphere were growing and it prompted other scientists to conduct similar studies. NASA says that 97 percent of scientists agree that humans are causing global warming and climate change.

The Keeling Curve has continued uninterrupted and updates daily. You can see a snapshot of the full record below, or visit The Keeling Curve curve in action, thanks to UC San Diego and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. It provides an indisputable visual look at the increase of CO2 in our atmosphere since 1960.

It took another 30 years after Keeling started his measurements before Dr. James Hanson sounded the alarm on climate change during his1988 testimony to the US Senate. He told senators that he was 99% sure climate change was affecting the planet.

“‘It is time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here,” Hansen told reporters following his testimony.

Another twenty-seven years later, more than 190 countries from around the world signed the Paris Agreement and pledged to reduce their carbon emissions to stay below 1.5 0C of global warming. The agreement included flexibility mechanisms to allow trading of credits based on reductions against a baseline of emissions and it set the stage for today’s carbon credits markets. Carbon Brief provides a chronology of carbon offsets here.

And last year, Dr. Hanson and fellow colleagues wrote that they now believe the planet may warm faster than previous estimates.

It took us until we really experienced the effects of climate change before we started doing much about it. Warming oceans, shrinking Antarctic Sea ice, wildfire smoke, floods and droughts seem to have finally caught human attention. Then the problems brought on by climate change started to affect the industrialized world’s pocketbooks, from grocery bills to insurance coverage, and that seemed to finally add urgency to the issue.

If you’re wondering why the history lesson? Here are three reasons:

1. To remind everyone that the climate crisis didn’t “just happen overnight.” The world has known about the problem for years and spent most of that time researching, arguing over and deflecting the impact of climate change.

2. Our collective kick-the-can-down-the-road attitude toward climate change prompted a surge of activity in the carbon credits market, and that was spurred on by another human trait – our tendency to look for a quick-fix.

3. The simple idea that we should learn from our past, not repeat the same mistakes, and take positive action to address the climate crisis. In other words, do things the right way.

The 2019-23 surge and struggle in the carbon credits market

As more people became directly affected by global warming, they started to blame industrialized countries and the businesses within them. The fossil fuel industry became a primary target. Then came manufacturing, transportation, agriculture, electrical power, and nearly every business in the industrialized world.

People were now sounding the alarm and pushing businesses to act. It was 2019.

Back then, a colleague of mine and I were breeding plants and came up with an interesting discovery. One plant captured and stored significantly more CO2 than others. We cultivated this plant in different locations and tried a variety of techniques to improve the speed, yield and the carbon capture and sequestration of our process. It worked, and I started buying and leasing land to start projects with the idea of capturing carbon and selling credits.

At about the same time, an Argentinian entrepreneur started a company called Pachama. His idea was to sell carbon credits based on preventing deforestation. In this case, owners of threatened forests offered to protect them, and claimed that additional carbon would be absorbed by trees that would have been cut down. Funding for this protection came from companies that wanted to offset their own CO2 output and allow them to claim to reduce their overall carbon footprint. The benefits of these projects, known as REDD (reducing emissions from deforestation in developing countries), were certified by Verra, a company considered to be the world’s leading certifier.

It seemed like a quick and simple solution and Pachama sales began to take off. But there was a problem. Pachama couldn’t keep up with demand and it led to cutting corners. Pachama appeared to sell credits from forests that were not under threat at all, and Verra certified them.

This scheme was exposed in a 2023 story by The Guardian, and the headline, “Revealed: more than 90% of rainforest offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows,” marked a black eye on the carbon credits markets. Several large companies were accused of greenwashing and the market lost credibility. Verra refuted the claims in the article and they have worked with Pachama since to improve their reporting and verification practices.

Throughout this time span, we increased the number of our projects, which are focused on farming and not deforestation, and continued to invest in research and development. Our third-party verified projects continue to show that our methods capture and sequester significantly more carbon than trees as well as replenish the soil.

An encouraging turning point in the carbon credits market

On May 28, Biden-Harris administration officials released a Joint Policy Statement and Principles on Voluntary Carbon Markets. The seven principles called for carbon credits that notably provide measurable decarbonization and transparency to improve market integrity.

I welcome this announcement, since it’s in-line with our projects. As noted at the start of this post, we begin each project by establishing a baseline of carbon currently captured and stored in the soil, and proceed with our MRV (measurement, reporting, verification) processes. This work ensures that we generate “high integrity” carbon credits, which is what the administration’s joint policy statement called for.

Yet another argument

The Biden-Harris announcement was applauded by many, but it did shine a light on yet another debate, this time about the use of credits to offset a portion of a company’s Scope 3 emissions, which are those generated by suppliers and customers.

In April, the UN-backed Science Based Target Initiative (SBTi), an organization that was created to help companies set emissions reduction targets based on climate science and Paris Agreement goals, announced that carbon credits could be used to abate Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions. Some argued to allow carbon credits for Scope 3 emissions and others argued against it. The dust up created so much controversy that SBTi’s CEO, Dr. Luiz Amaral, announced that he’d step down at the end of this month.

My position on Scope 3 carbon offsets

Personally, I’m for the use of carbon credits to offset Scope 3 emissions, and not simply because they help my business. My reasons are based on scientific research saying that the climate crisis is getting worse, coupled with my understanding of the economic realities of the biggest industry in my state.

Here in Michigan, automotive manufacturing is the major industry, contributing more than $300 billion to the state’s economy each year. Some 96 of the top 100 suppliers to North America have a presence in Michigan and 60 are headquartered here. There are many, many more lower tier suppliers, companies that would be considered Scope 3, who supply parts and services to larger suppliers and ultimately to vehicle manufacturers.

For years, these Scope 3 companies, some of which are run by friends of mine, have been under intense pressure from customers to innovate, improve quality and cut costs. As a result, these companies’ margins have been squeezed so thin that even the most well-intentioned companies have a tough time financing projects to offset their own emissions or buy carbon credits. I’m sure this situation is similar in other industries across the country and around the world.

If large companies can afford to buy carbon credits to offset Scope 3 emissions, let them. We need to reduce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in our atmosphere, and we need to do it fast. Abatement projects need to be funded and funding should be encouraged for Scope 3 emissions.

Meanwhile, governments, banks and other financial institutions should work on ways to help smaller, so-called Scope 3 companies to develop and finance projects to cut their direct emissions.

Good signs for the future

Following the US announcement at the end of May, three things happened in the past month that demonstrate a sense of urgency in re-igniting the carbon credits market.

First, Mark Maslin, professor of natural sciences at University College London and a founding member of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group, suggested five ways to improve the global voluntary carbon credits markets. Maslin’s five include: 1. Increase transparency; 2. Improve accreditation; 3. Credits should do no harm; 4. Focus on high-quality credits; 5. More international support. I agree with each of these suggestions and believe it starts with quality.

Second, six of the most influential environmental non-governmental organizations announced their support of limited, high-quality carbon credits for Scope 3 emissions abatement in a letter to the Science Based Targets Initiative, the UN-backed organization that was set up to help companies set emissions standards that are inline with climate science and Paris Agreement goals. They also acknowledge that “the private sector will be key to reach our climate goals and SBTi’s role has been pivotal.”

Third, ISO, the International Organization for Standardization, announced that they will develop the first international standard on net zero, and it’s expected to launch next year at COP30. “The standard will give the public greater confidence and guard against greenwashing by setting out robust guidance and requirements offering the potential to verify the credibility of claims,” ISO wrote on its website. And they’ve invited experts to participate in the development of the standard by applying to “join their National Standard Body’s climate change management committee by finding their country’s ISO member.” I encourage you to do so. I will.

I’m encouraged to see the industry coalescing around the development of new and improved standards and reporting. It will lead to a resurgence of high-quality carbon abatement projects and the carbon credits markets that fund them.